Aligning the economic incentives of a manager with the competing objective of investors, who wish to maximize value/returns, is critical to the success of any fund. This is best accomplished by well-constructed “fund economics,” the manner by which the returns of a fund are allocated amongst its various stakeholders.

In this article, we provide important background information on fund economics and a high-level explanation of the terms commonly used in its construction.

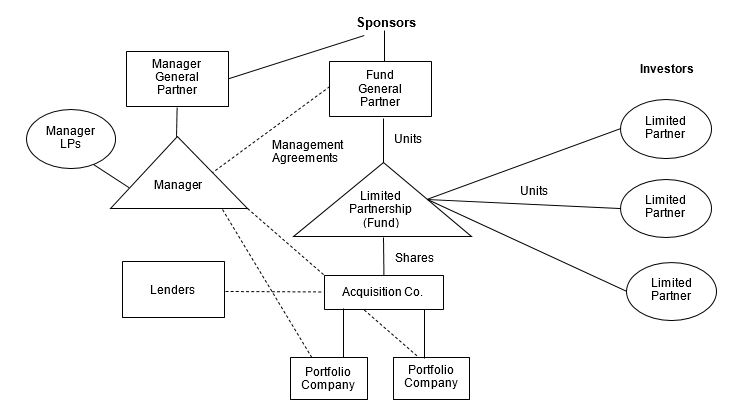

Before turning to that, however, let us consider a simplified PE fund structure to identify some of the more common parties involved in a limited partnership structured fund.

Simplified PE Fund Structure

1. Fully Funded vs Committed Capital

Funds are generally characterized into two categories: those that are fully funded and those where capital is merely committed. The distinction between these two types of funds is a function of when the fund is capitalized. Fully funded funds are capitalized at the time of their inception. By contrast, committed capital funds are partially capitalized at inception, with the commitment by LPs to capitalize the remaining amount later.

A “fully funded” fund typically starts with sponsors finding an investment target (e.g., portfolio company) that they wish to acquire. They then approach investors (LPs) to contribute capital and lenders (banks or alternative lenders) to provide debt to fund the acquisition (purchase price and expenses) of the portfolio company — in such a case, only one portfolio company would be illustrated in the diagram above. In this manner, the funding and acquisition occur at the same time and each fund stands alone for that particular acquisition. This approach is sometimes used by less experienced sponsors who are in the process of establishing themselves. In a fully funded model, the manager charges fees based on the capital provided by investors at the outset.

By contrast, and as noted above, investors in a “committed capital” fund commit to delivering the funds they have agreed to provide over the investment period of the fund. The manager makes “capital calls” from time to time, obliging investors to deliver funds to finance the fund’s transactions. Typically, investors in a committed capital fund rely on the sponsor and/or manager to deploy funds how and when required. The expertise and track record of these parties is an important factor for investors when determining whether, and how much, to invest, particularly as an investor has no ability to liquidate their investment in a fund, other than in extraordinary circumstances.

2. Management Fees and Carried Interest

Management fees are typically paid to a fund manager on an annual basis to cover the manager’s costs of managing the fund and the costs associated with seeking out and evaluating investment opportunities. Managers may also receive fees from portfolio companies for the provision of managerial services. Management fees may initially be charged on committed capital during the investment period, and then “step-down” to the invested capital after the investment period has expired.

Funds also typically pay a sponsor a share of the profit, known as a “carried interest.” The carried interest (or, the “carry”) is payable to the sponsor after an agreed preferred return is provided to investors. Carried interest is the sponsor’s portion of any profits that their investments made above the contributed capital returned to and preferred returns earned by investors.

The amounts of the fees, hurdle rates, and percentage of carry can vary depending on the manager’s and sponsor’s role in the fund, including its role in sourcing and structuring the deal(s) for the fund. Discounted management fees are also sometimes offered to early investors or to investors committing larger amounts of capital to a fund.

3. The Distribution Waterfall

One of the most important economic provisions for private equity funds is what is referred to as the “waterfall.” A waterfall provision establishes the pecking order by which profits and losses are divided amongst participants of the fund as and when funds become available (although in some limited circumstances a fund may allow for funds to be reinvested and not distributed). Generally, funds structure their distribution waterfalls based one of two models. The “fund-as-a-whole” model (also known as the “European” model) calculates return of capital, preferred return, and carried interest on all capital contributions made by investors. Though distributions may be customized in accordance with a particular fund’s needs, distributions under a “fund-as-a-whole” carried interest structure are commonly allocated in the following order of priority:

- Return of Capital: first, 100% to investors until they receive an amount equal to their aggregate capital contributions;

- Preferred Return: second, 100% to investors until they receive an amount equal to their preferred return (also known as the hurdle rate), which is agreed to at the outset of the fund;

- Catch-Up: third, 100% to the sponsor until they receive a certain percentage of the distributable capital equal to their agreed percentage; and

- Carried Interests: finally, any remaining distributable capital is divided in accordance with the carried interest rate between the investors and the sponsor.

By contrast, other funds are structured as “deal-by-deal” (also known as “American”) carry. In a “deal-by-deal” structure, carried interest is paid after the capital contribution and return is paid on each individual deal. “Deal-by-deal” carried interest structures are more favourable for the sponsors, as they will receive their carried interest earlier, as they do not have to wait until all capital contributions have been returned to investors.

4. Clawback Provisions

In certain circumstances, fund sponsors may receive carried interest payments in excess of their overall carried interest entitlement (for example, where the carried interest is paid out on a deal-by-deal basis). When this occurs, an adjustment mechanism called a “clawback provision” serves as a protective mechanism for private equity fund investors by requiring sponsors to pay back to the fund any excess carry they received. Clawback provisions often address the following factors:

- the timing of clawback payments;

- certain tax considerations, such as whether to limit the clawback to the after-tax amount of the carry; and

- what resources are available to satisfy the clawback (i.e., escrow and guarantees).

These factors, and others, should be carefully considered by in any committed capital fund where the carried interest payment could result in overpayment.

Finally, companies lacking internal expertise in these matters should consider seeking guidance from external experts. As always, the Cassels Private Equity Group is available to provide advice and assistance to businesses navigating these considerations.