Indigenous participation and benefit agreements which address mine development have become commonplace across Canada. Often referred to as “Impact Benefit Agreements” or “IBAs,” these agreements are increasingly expected by regulators, and in some cases even mandated by law. But while many mining proponents recognize their importance, reaching what both parties believe to be a “fair deal” can often be a lengthy and challenging process.

2023 will mark eight years since the Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act (ESTMA) came into force, and six years since it first applied to “Aboriginal governments.” ESTMA requires publicly listed Canadian companies, as well as foreign companies with significant operations in Canada, to make annual public disclosures of payments to governments, including “Aboriginal governments.”

The increase in both the volume and quality of ESTMA reporting over the past few years has created new opportunities to benchmark and evaluate IBA terms. This data has the potential to help both mining proponents and Indigenous governments assess what constitutes a “fair deal” when comparing against similar projects, promote trust in negotiations, and add a level of objectivity to the negotiation of Impact Benefit Agreements.

The Importance of a “Fair Deal”

Understanding whether an Impact Benefit Agreement is “fair” is typically a major consideration for both the Indigenous party and the mining proponent.

Indigenous government leadership are accountable to their members/citizens when entering into agreements. Indigenous governments which use a member ratification process will ultimately need to convince their members that the negotiated terms are fair. And some Indigenous governments view their reputation for resolving fair terms with proponents as a part of a larger economic strategy aimed at attracting and benefiting from resource development.

Similarly, proponents are accountable to their shareholders. For foreign-owned companies, there may be a need to explain to unfamiliar foreign executives how IBA terms under negotiation are fair and reasonable in the local Canadian context. Proponents also often face the challenge of negotiating with a number of Indigenous communities in respect of the same project, and understanding what constitutes “fair” can help when managing competing interests and expectations.

There are, of course, exceptions where fairness is not a shared objective. Where the proponent’s ability to minimize costs is a major motivating factor or even essential to advancing the project, or where an Indigenous party believes that comparisons to other IBAs are not appropriate given their specific circumstances or their community’s objectives. However, even in these circumstances, comparative IBA information can provide useful data for defining and assessing these objectives.

Opportunities with Data

While five years of ESTMA reports showing payments to “Aboriginal governments” are available, the value of these reports in the initial few years was limited. ESTMA reports present amounts paid in a period, but rarely disclose the context necessary for understanding how those amounts arose or were calculated, providing limited visibility to the content of underlying agreements.

Understanding the content of IBAs requires more than a snapshot for a single year. Payments may be lumpy from one year to another due to the way in which they are calculated. Many IBAs provide for milestone payments leading up to commencement of production, while some provide for an increase in revenue sharing after certain development costs are repaid. With the agreements themselves typically kept confidential, and often little or no description provided to explain the of the nature of the payment reported under ESTMA, it had been challenging to develop robust comparison sets in the first few years of mandatory ESTMA reporting. In addition, from the author’s experience, the quality of reporting seems to have improved over time. In some cases, Indigenous communities or related entities which appeared to have been overlooked in early years have been included in more recent reports – potentially identified as accounting departments became more familiar with the reporting process.

On their own, the ESTMA reports are a valuable tool for indicating project cashflow to Indigenous nations, and for helping proponents understand the experience of the Indigenous community they are negotiating with. ESTMA reports also shed light on neighbouring communities’ experiences, which may inform expectations.

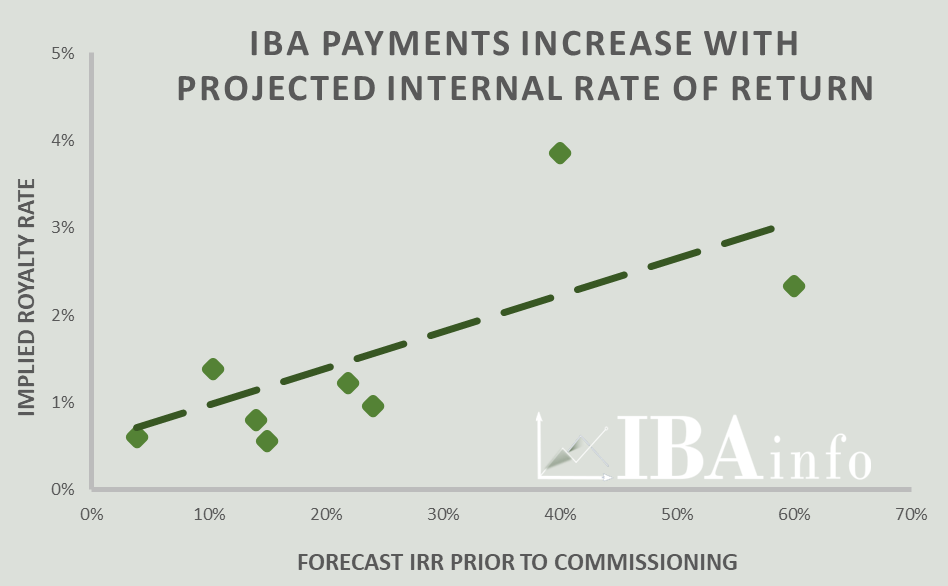

Perhaps the greatest opportunity presented by ESTMA is when the payments information is integrated with other publicly available project information. For example, by comparing ESTMA data to financial statements, project payments can be understood as a proportion of profits and revenues, and in some cases distinctions can be made between variable and fixed payments. Similarly, by examining National Instrument 43-101 reports issued during the presumed period of negotiation (Impact Benefit Agreements are often publicly announced when signed), correlations can be drawn between the perceived value of a project prior to construction (such as internal rate of return or net present value) and the financial contributions shared with Indigenous communities under the IBA, providing an understanding of what constituted a “fair share” in the context of that project.

Performing this analysis in respect of specific projects (for example, nearby projects or projects which are considered reasonable precedents) is fairly straightforward. However, by analyzing broader industry datasets, projects can be assessed across a variety of variables, such as profitability, size, location, and resource. While each IBA addressed unique circumstances, an industry-wide approach can help identify exceptions and overall trends.

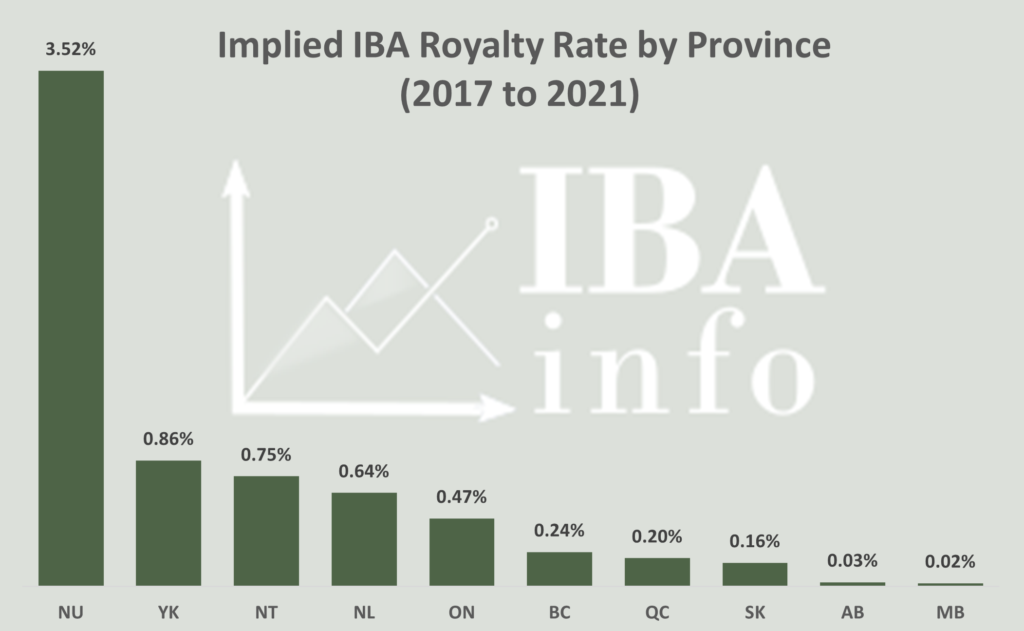

Payments to Indigenous Organizations as a Percentage of the value of mining shipments, as measured using ESTMA reporting. Source: IBAInfo.org.

For an industry-wide perspective, some interesting insights and charts that have been generated from ESTMA and other public data are available on IBAinfo.org (Arend Hoekstra is an occasional contributor to IBAInfo.org). They indicate that the value of IBAs often track the value of projects. Likewise, similar projects in different jurisdictions may have differing agreements, potentially in reflection of regulatory and other factors which can inform negotiations. This data can also help identify if there are typically premiums paid for the extraction of gold, diamonds, uranium or coal in reflection of their differing potential environmental impacts.

ESTMA reported payments as a share of disclosed revenue the years 2019 and 2020 as compared to the forecasted internal rate of return for a project as disclosed under National Instrument 43-101 prior to project commissioning. Source: IBAInfo.org.

Where proponents undertake their own assessments, extra precautions should be made when gathering data. StatsCan has taken some steps to summarize the ESTMA datasets, however at the moment these seem to suffer from some data integrity issues.

Putting Data into Practice

Below are several ways in which comparative reports developed with ESTMA and other data (Reports) can be used in the process of negotiations:

- Preparation: Obtaining a Report, whether it is commissioned or developed in-house, can be a helpful first step in preparing for IBA negotiations. These Reports can help prepare leadership expectations around negotiations, and may help preliminary internal discussions around the overall “pot” available when dealing with multiple Indigenous parties.

- Sharing: In some instances, proponents may wish to share their market Reports with their Indigenous counterparts to build trust or to address impasses. This approach may be most effective where there is only one main impacted Indigenous community, or where all of the Indigenous parties are negotiating collectively; in instances where a number of Indigenous parties are negotiating separately, sharing a market Report may instead lead to challenging discussions around the appropriate allocation among Indigenous communities.

- Advocating in Mediation / Arbitration / Litigation: In the course of negotiating an IBA, the parties may seek to include a mediator or an arbitrator. Having comparative data set out in a Report can be helpful in advocating for a proponent’s position in these circumstances. Similarly, it is not uncommon for proponents to provide some form of contractual commitment to negotiate an IBA in respect of a mine. Being able to show the reasonableness of the proponent’s negotiation position (including to a court) may be a relevant factor to discharging these obligations.

Anticipating Challenges

While using comparative data, including ESTMA reports, can be helpful in negotiations, there are limitations. The data may not reflect all relevant Indigenous negotiation priorities, such as real, potential, and perceived impacts of a project on communities and their Aboriginal and treaty rights. However, incorporating information about the type of mine (open pit vs underground, coal vs diamond) or condition (brownfield vs greenfield) can provide some guidance, at least in terms of the physical environmental impacts.

Similarly, and as noted above, Impact Benefit Agreements for the same project can vary significantly between Indigenous communities, including due to proximity of the community to the project, community size, connection to the lands, and regulatory leverage. Comparative data (including from ESTMA) is more valuable when assessed on an aggregate basis for all IBA payments made in respect of a Project, and may not be as useful in respect of assessing IBA payments made to individual communities. When planning for benefit negotiations, proponents may want to start with the mine-level assessment, and then move to much more subjective tools and considerations to assess what is reasonable on an individual Indigenous community level.

Final Thoughts

The process for negotiating and arriving at Impact Benefit Agreement terms has been opaque for decades. Negotiating parties have been highly reliant on hearsay and the advice of experienced professionals. This opacity has added tensions and challenges to the already complicated process of seeking to reconcile the interests of Indigenous communities and proponents.

While each negotiation is unique, and there will always be parties that claim that past agreements are outdated and irrelevant, the analysis of publicly available comparative information presents a significant opportunity for the majority of parties that are interested in building trust and achieving a fair result. That opportunity has the further potential to reduce costs and delays, promote transparency, create consistency, and potentially advance reconciliation.